The bunionette deformity—evaluation and management

Introduction

The term “bunionette” refers to a prominence of the lateral aspect of the fifth metatarsal head, which may or may not be symptomatic. Historically, bunionettes have been referred to as “tailor’s bunion” due to the prevalence amongst tailors, who sat cross-legged all day with the lateral edge of their feet rubbing on the ground. Patients with bunionette deformity have been found to specific risk factors predisposing them to this deformity. While many of these may be treated conservatively, some patients may continue to experience pain and disability and require surgical intervention.

Anatomy and pathophysiology

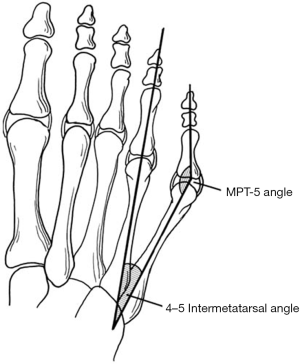

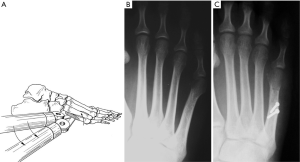

Symptomatic bunionette deformities have been associated with anatomic variants. Coughlin previously described several anatomic factors that may contribute to the painful condition. These include prominence of the metatarsal head, congenital plantarflexed or dorsiflexed metatarsals, increased four to five intermetatarsal angle (IMA), and lateral bowing of the metatarsal shaft (1,2). These variants led to the creation of a classification system which will be discussed later. Typically the toe is adducted compared to the metatarsal (Figure 1). Other congenital deformities such as splayfoot and brachymetatarsia have been linked to development of bunionette deformities (3,4). Soft tissue abnormalities may accompany bunionette deformities (3,4). Plantarflexed metatarsals, ankle and hindfoot deformities are associated with plantar callosity and increased pressure against shoe wear (5).

Evaluation

Bunionette deformity is more common in women than men with varied ratios reported in the literature from 2:1 to 10:1 (6-10); bilateral deformity is common (7). Patients with bunionette deformities tend to present with pain at the lateral forefoot, which is generally exacerbated by closed shoe wear. Some patients may have more pain in the plantar-lateral forefoot than directly lateral. Other metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint pathologies should be ruled out during evaluation. Inflammatory, crystal and non-inflammatory arthropathies must be rules out as well. If inflammatory arthritis is suspected, rheumatoid nodules may be evaluated with MRI or ultrasound to evaluate extent of the disease. The deformity and prominence in these cases results from chronic synovitis, which causes capsular distension (11). Additionally, chronically inflamed bursal tissue may develop lateral to the osseous prominence, worsening the clinical picture.

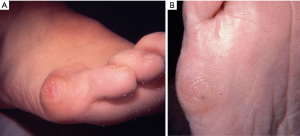

A complete foot and ankle examination are critical to defining the exact pathology and to identify other co-existing pathologies that may require treatment. Physicians should look for hindfoot valgus and pes planus (1,2,12). Splayfoot deformity arises when there are coexisting hallux valgus and bunionette deformities (3). In a series by Coughlin looking at bunionette correction, 60% of patients required correction of additional deformities including hallux valgus, hallux rigidus, and hammertoe deformities, among others (30%, 10% and 7%, respectively (8). Skin and subcutaneous tissue examination is critical. Lateral eminence swelling with either erythema, keratosis, ulceration or callosity must be evaluated. Callosity may present laterally or plantar (Figure 2). In the cases in which these lesions extend to the plantar surface, the surgical plan should consider elevation of the metatarsal head in addition to medialization (5,13).

Radiographic evaluation begins with standard weight-bearing radiographs with anterior posterior and lateral views. Several angles have been described in the assessment of bunionette deformity. Most commonly, the 5th MTP joint angle (MTP-5 angle), the 4–5 IMA and the fifth metatarsal lateral deviation angle are calculated (Figure 3). Average MTP-5 angle is 10.2, while 90% of normal feet have an angle of 14 degrees or less (14).

The MTP-5 angle demonstrates the medial deviation of the toe in relation to the metatarsal shaft. The average angle in normal feet has been shown to be 10.2 degrees and in 90% of normal feet, the angle is 14 degrees or less (7,14). Symptomatic bunionettes averaged an MTP-5 angle of 16 degrees or more (5,7,8). Another angle commonly used is the 4–5 IMA. This angle measures the divergence of the 4th and 5th metatarsals. By drawing a line through the axis of each metatarsal, the 4–5 IMA angle is the angle at the intersection of these lines. The most common method to bisect the axis of the metatarsal is to use a line on the medial and lateral margins of the proximal metaphysis and the metatarsal neck (5,7,15). The average of the 4–5 IMA angle was to found to be 10.8 degrees (7). On the other hand, Fallat and Buckholz stipulated that the most consistent anatomic way to determine the axis of the 5th metatarsal shaft is to use a line adjacent and parallel to the medial surface of the proximal half of the metatarsal shaft (6). They found a difference in about 2 degrees comparing normal feet (6.5 degrees) to feet with bunionettes (8.7 degrees). Interestingly, they noted a change in 4–5 IMAs when foot position goes from inversion to eversion; noting a change of 3 degrees in 4–5 IMAs (6). When considering all the studies available, consensus seems to settle on abnormal 4–5 IMAs values equal to or greater than 9 (5).

Another possible contributor to the development of a painful bunionette is an excessive lateral bowing of the fifth metatarsal shaft. (1,5,8,16,17). The 4–5 IMA may be normal in these patients, but a lateral curvature of the 5th metatarsal diaphysis is culprit of the deformity. Fallat and Buckholz defined this measurement as the angle created by a line parallel and adjacent to the proximal medial surface of the fifth metatarsal and a line representing the axis of distal metatarsal using bisecting points of the medial and lateral head and neck (6). Contrary to Nestor et al. (7) who did not find a difference in lateral bowing between symptomatic bunionettes and controls, Fallat and Buckholz found an average lateral bowing of 8.1 degrees compared to controls (2.6 degrees) (6). According to Cooper et al, the estimated incidence of patients who undergo surgery for symptomatic bunionettes who present with bowing of the 5th metatarsal shaft ranges from 10% to 23% (5). Lastly, the width of the 5th metatarsal head also contributes to symptomatic bunionettes. The normal width of the 5th metatarsal head is about 13 mm, with a variance ranging from 11 to 14 mm (6,18). The estimated incidence of an abnormally large metatarsal width ranges from 16% to 33% (5).

Classification

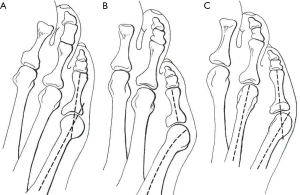

Using these radiographic parameters, Coughlin suggested a classification system for bunionettes that is widely used today (Figure 4) (8). Type 1 refers to an enlarged 5th metatarsal head, Type 2 refers to normal 4–5 IMA with an increased lateral bow of the 5th metatarsal shaft, and type 3 refers to an increased 4–5 IMA. Type 3 is the most common type in symptomatic bunionettes; making the 4–5 IMA the most believed factor to play a role in symptomatic bunionettes (5).

Nonoperative treatment

There is limited literature regarding successful nonsurgical treatment options for symptomatic bunionettes. Shi et al. believe that <90% of patients with symptomatic bunionette deformities resolve without invasive procedures (2). Nevertheless, non-operative treatment should be attempted prior to surgery. For the most part, non-operative management revolves around symptomatic treatment of pain and callous formation. Shoe wear modification may help patients with pain control by using wider toe box shoes. Callous management with protective pads and shaving may control some of the symptoms. Grice et al. showed an improvement in lesser toe MTP joint synovitis pain with corticosteroid injection over a period of 2 years (19). Nonetheless, no long term studies have shown improvement of symptoms with non-surgical management.

Operative treatment

Operative management of bunionette deformities depends greatly on the nature of deformity. The classification system of bunionette deformities aids physicians in establishing an algorithm that can be used to address these deformities. The available options for surgical management include: metatarsal head resection, distal chevron osteotomies, subcapital oblique osteotomies, proximal or midshaft oblique osteotomies, Scarf osteotomy, Ludloff variant osteotomy, among others.

In our experience, metatarsal head resection is only reserved for unhealthy patients, or in those patients with an infectious or inflammatory process, as this procedure has been associated with poor outcomes. Kitaoka et al. reported poor results in a case series of 11 patients undergoing metatarsal head resections with a follow up of 8 years (20). The poor outcomes reported included transfer metatarsalgia, persistent lateral forefoot prominence and painful fifth toe deformity. In their conclusions, they recommend against the use of metatarsal head resections. Nonetheless, metatarsal head resection does have a role in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Reize et al. demonstrated in a retrospective study of 56 rheumatic feet successful results in terms of cosmetic and functional outcomes as well as pain control (21).

Distal chevron osteotomies are a popular technique to address Type I bunionette deformities. Kitaoka et al. reported a case series of 19 distal chevron metatarsal osteotomies and a 7 year follow up with good outcomes without failures (22). IMA 4–5 angle, MTP 5 angle and forefoot width were all improved at follow up. They reported one case of transfer metatarsalgia and one case of wound infection. Boyer and Deorio reported good outcomes in 12 distal chevron osteotomies fixed with a PDS pin. They showed radiographic union in all patients and high patient satisfaction (23).

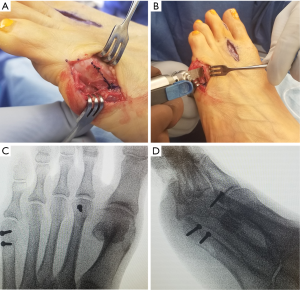

Another reported technique for management of type I bunionette deformities is the subcapital oblique osteotomy (Figure 5). Cooper and Coughlin demonstrated, in a retrospective review of 16 feet with a follow up of approximately 3 years, reliable clinical results for correction of type I deformities (16). They reported improvement in patient satisfaction, pain control; however, there was no significant improvement in IMA 4–5 angle at post-operative evaluation. We have found this procedure to have more flexibility than the chevron osteotomy. In addition to translating the metatarsal head laterally, by angling the saw blade slightly, the metatarsal head may be elevated to alleviate plantar pressure as well.

When addressing increased IMA 4–5 angles or increased lateral bowing, diaphyseal osteotomies are preferred. Adapted from hallux valgus surgery, Coughlin described an oblique osteotomy of the metatarsal shaft (similar to the Ludloff osteotomy described for hallux valgus), in conjunction with lateral condylectomy and distal MTP realignment to correct bunionette deformities (Figure 6). In his study, Coughlin reported 93% of good or excellent outcomes in 30 feet treated in this manner (8). Recently, Waizy et al. demonstrated improvement in patient satisfaction, radiographic measurements of IMA 4–5 angle and lateral bowing with a reverse Ludloff osteotomy for type II and type III bunionette deformities. They reported no complications or revisions from their procedure (24). Shi et al. documented several studies who reported similar outcomes with Ludloff variants and scarf osteotomies for type II and type III bunionette deformities (2).

Although they have been described, very proximal fifth metatarsal osteotomies are discouraged secondary to concerns of nonunion. The blood supply to the proximal metaphyseal-diaphyseal region is tenuous, and the stresses on the bone are higher in this region, which may contribute to poor healing. Nevertheless, some surgeons continue to use it to address bunionette deformities with increased IMA 4–5 angles. Okuda et al. reported a case series of 10 feet treated with a proximal dome shaped osteotomy with significant improvement in MTP 5 angle and IMA 4–5 angles (25). The results were reported as good in all 10 patients. However, there were 3 cases of delayed at the osteotomy site. Importantly, they noticed that all 3 cases of delayed union had osteotomies that were more proximal than those with expected union rates; hence, they advise caution with osteotomy sites that are too proximal.

Recently, minimally invasive surgical techniques have been popularized for a number of foot and ankle conditions. Giannini et al. (26) found excellent results using a transverse distal metatarsal osteotomy, performed for type II and III deformities. Contrary to this, Waizy et al. (27) described their results using a similar technique in 31 feet. They found good to excellent results in 16 feet, satisfactory in 14, and poor results in 9, with inferior results for type II and III deformities. They recommend using this technique only for type I deformity.

The post-operative care varies across the literature. Some surgeons opt to maintain non-weight bearing precautions until 6 weeks. The foot is placed in a splint following surgery and transitioned to a short leg cast until post-operative week 6. At that point patient is allowed to progress weight bearing activities in a post-operative shoe and expected to return to normal activities at 8–10 weeks. The authors’ preference of post-operative protocol involves immediate heel-weight bearing in a post-operative shoe until week 6. At that point, the patient is typically allowed to progress to full weight bearing and expected to return to normal activities between 8–10 weeks post operatively.

Complications

Correction of bunionette deformity has an overall low complication rate (2). Some of the complications faced by surgeons include: malunion, nonunion, avascular necrosis, transfer metatarsalgia, recurrence and wound complications. Nonunion and avascular necrosis may be secondary to significant soft tissue stripping during surgical approaches. Nonunion and malunion are also affected by instability at the osteotomy sites from either poor or lack of internal fixation. As reported in proximal osteotomies, extension of the proximal osteotomy into watershed areas may increase risk of delayed union. Due to the small size of the metatarsal, distal osteotomies are at risk of instability with poor fixation or overcorrection. Chevron osteotomies translated >50% may lead to instability. Transfer metatarsalgia may occur if the fifth metatarsal is excessively elevated or shortened. The sural nerve or lateral dorsal cutaneous nerve is at risk with any bunionette procedure and must be protected. Malagelada et al. (28) found the nerve to have variability and described safe zones to protect it during minimally invasive techniques. Lastly, recurrence of deformity is seen in all types of bunionette deformity when the procedure of choice fails to address the underlying driver of the deformity. Adequate understanding of the types of deformities and the corresponding surgery will minimize chances of recurrence.

Conclusions

Although less common than hallux valgus and other forefoot disorders, bunionette deformity may be a source of significant pain and disability. Proper evaluation requires close examination of the entire foot and ankle. Initial treatment should focus on symptomatic relief. However, when this fails, several surgical options are available. With proper surgical selection and technique excellent outcomes may be obtained.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflict of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aoj.2019.10.03). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Coughlin MJ. Etiology and treatment of the bunionette deformity. Instr Course Lect 1990;39:37-48. [PubMed]

- Shi GG, Humayun A, Whalen JL, et al. Management of Bunionette Deformity. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2018;26:e396-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bishop J, Kahn A, Turba JE. Surgical correction of the splayfoot: the Giannestras procedure. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1980;234-8. [PubMed]

- Schimizzi A, Brage M. Brachymetatarsia. Foot Ankle Clin 2004;9:555-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cooper MT. The Bunionette Deformity: Overview and Classification. Tech Foot Ankle Surg 2010;9:2-4. [Crossref]

- Fallat LM, Buckholz J. An analysis of the tailor’s bunion by radiographic and anatomical display. J Am Podiatry Assoc 1980;70:597-603. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nestor BJ, Kitaoka HB, Ilstrup DM, et al. Radiologic anatomy of the painful bunionette. Foot Ankle 1990;11:6-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coughlin MJ. Treatment of bunionette deformity with longitudinal diaphyseal osteotomy with distal soft tissue repair. Foot Ankle 1991;11:195-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schabler JA, Toney M, Hanft JR, et al. Oblique metaphyseal osteotomy for the correction of Tailor’s bunions: a 3-year review. J Foot Surg 1992;31:79-84. [PubMed]

- Haber JH, Kraft J. Crescentic osteotomy for fifth metatarsal head lesions. J Foot Surg 1980;19:66-7. [PubMed]

- Brooks F, Hariharan K. The rheumatoid forefoot. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2013;6:320-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ceccarini P, Rinonapoli G, Nardi A, et al. Bunionette. Foot Ankle Spec 2017;10:157-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cooper MT, Coughlin MJ. Subcaptial Oblique Fifth Metatarsal Osteotomy Versus Distal Chevron Osteotomy for Correction of Bunionette Deformity. Foot Ankle Spec 2012;5:313-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Steel MW, Johnson KA, DeWitz MA, et al. Radiographic Measurements of the Normal Adult Foot. Foot Ankle 1980;1:151-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schoenhaus H, Rotman S, Meshon AL. A review of normal inter-metatarsal angles. J Am Podiatry Assoc 1973;63:88-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cooper MT, Coughlin MJ. Subcapital oblique osteotomy for correction of bunionette deformity: medium-term results. Foot Ankle Int 2013;34:1376-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yancey HA. Congenital lateral bowing of the fifth metatarsal. Report of 2 cases and operative treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1969;203-5. [PubMed]

- Zvijac JE, Janecki CJ, Freeling RM. Distal oblique osteotomy for tailor’s bunion. Foot Ankle 1991;12:171-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grice J, Marsland D, Smith G, et al. Efficacy of Foot and Ankle Corticosteroid Injections. Foot Ankle Int 2017;38:8-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kitaoka HB, Holiday AD. Metatarsal head resection for bunionette: long-term follow-up. Foot Ankle 1991;11:345-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reize P, Leichtle CI, Leichtle UG, et al. Long-term results after metatarsal head resection in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Foot ankle Int 2006;27:586-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kitaoka HB, Holiday AD, Campbell DC. Distal Chevron metatarsal osteotomy for bunionette. Foot Ankle 1991;12:80-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boyer ML, Deorio JK. Bunionette deformity correction with distal chevron osteotomy and single absorbable pin fixation. Foot ankle Int 2003;24:834-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waizy H, Jastifer JR, Stukenborg-Colsman C, et al. The Reverse Ludloff Osteotomy for Bunionette Deformity. Foot Ankle Spec 2016;9:324-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okuda R, Kinoshita M, Morikawa J, et al. Proximal dome-shaped osteotomy for symptomatic bunionette. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002;173-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giannini S, Faldini C, Vannini F, et al. The minimally invasive osteotomy “S.E.R.I.” (simple, effective, rapid, inexpensive) for correction of bunionette deformity. Foot ankle Int 2008;29:282-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waizy H, Olender G, Mansouri F, et al. Minimally invasive osteotomy for symptomatic bunionette deformity is not advisable for severe deformities: a critical retrospective analysis of the results. Foot Ankle Spec 2012;5:91-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malagelada F, Dalmau-Pastor M, Sahirad C, et al. Anatomical considerations for minimally invasive osteotomy of the fifth metatarsal for bunionette correction - A pilot study. Foot (Edinb) 2018;36:39-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Cooper MT, Granadillo VA, Coughlin MJ. The bunionette deformity—evaluation and management. Ann Joint 2020;5:7.